What are Chiari Malformations?

A Chiari malformation is when part of the cerebellum has descended below the foramen magnum (an opening at the base of the skull). The cerebellum is the lowermost part of the brain, responsible for controlling balance and co-ordinating movement.

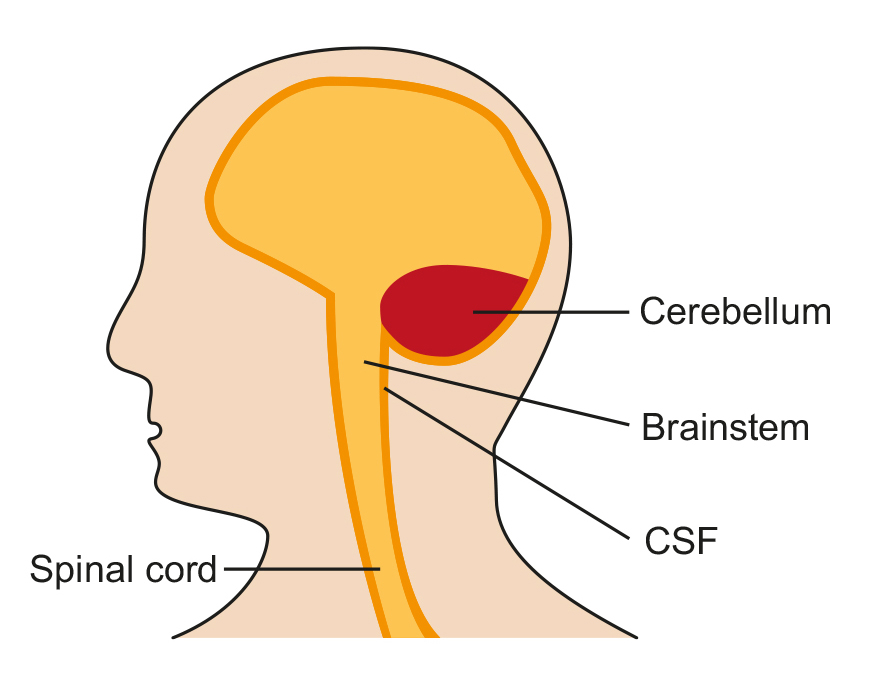

Normal formation of the brain

Chiari Malformations (CMs) are structural abnormalities of part of the skull that houses the cerebellum, the part of the brain that controls balance.

Normally, the cerebellum and parts of the brain stem sit in an indented space at the lower rear of the skull, above the foramen magnum (a funnel-like opening to the spinal canal). When part of the cerebellum is located below the foramen magnum, it is called a Chiari malformation.

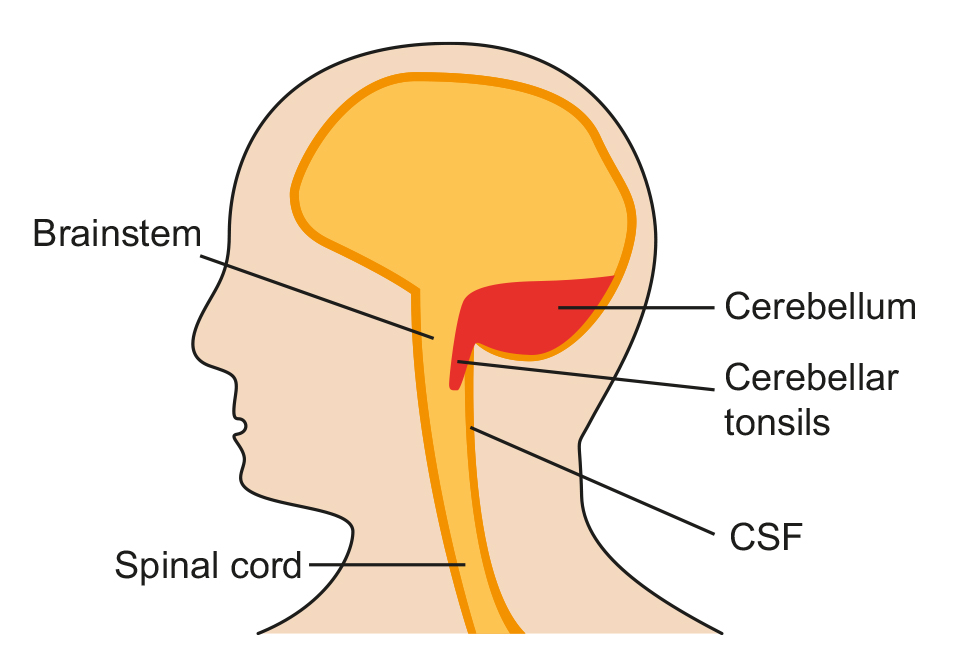

Type 1 Chiari Malformation

CMs may develop when the bony space is smaller than normal, causing the cerebellum and brain stem to be pushed downward into the foramen magnum and into the upper spinal canal. The resulting pressure on the cerebellum and brain stem may affect functions controlled by these areas and block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – the clear liquid that surrounds and cushions the brain and spinal cord – to and from the brain.

What causes these malformations?

CM has several different causes. It can be caused by structural defects in the brain and spinal cord that occur during foetal development (i.e. in the womb, before birth). This is called ‘primary’ or ‘congenital’ CM.

It can also be caused later in life if spinal fluid is drained excessively from the lumbar or thoracic areas of the spine; either due to injury, exposure to harmful substances, or infection. This is called acquired or secondary CM. Primary CM is much more common than secondary CM.

How are they classified?

CMs are classified by the severity of the disorder and the parts of the brain that protrude into the spinal canal.

Type I

Type I involves the extension of the cerebellar tonsils (the lower part of the cerebellum) into the foramen magnum, without involving the brain stem.

Normally, only the spinal cord passes through this opening. Type I – which may not cause symptoms – is the most common form of CM and is usually first noticed in adolescence or adulthood, often by accident during an examination for another condition. Type I is the only type of CM that can be acquired.

Type II

Type II, also called classic CM, involves the extension of both cerebellar and brain stem tissue into the foramen magnum. Also, the cerebellar vermis (the nerve tissue that connects the two halves of the cerebellum) may be only partially complete or absent. Type II is usually accompanied by a myelomeningocele; a form of spina bifida that occurs when the spinal canal and backbone do not close before birth, causing the spinal cord and its protective membrane to protrude through a sac-like opening in the back.

A myelomeningocele usually results in partial or complete paralysis of the area below the spinal opening. The term Arnold-Chiari malformation (named after two pioneering researchers) is specific to Type II malformations.

Type III

Type III is the most serious form of CM. The cerebellum and brain stem protrude, or herniate, through the foramen magnum and into the spinal cord. Part of the brain’s fourth ventricle, a cavity that connects with the upper parts of the brain and circulates CSF, may also protrude through the hole and into the spinal cord.

The covering of the brain or spinal cord can also protrude through an abnormal opening in the back or skull. Type III causes severe neurological defects.

Type IV

Type IV involves an incomplete or underdeveloped cerebellum – a condition known as cerebellar hypoplasia. In this rare form of CM, the cerebellar tonsils are located in a normal position but parts of the cerebellum are missing, and portions of the skull and spinal cord may be visible.

What are the symptoms of a Chiari malformation?

The main symptoms people with Type I malformations might experience are:

- Headaches (usually at the back of the head and often made worse by coughing, sneezing, straining or bending over).

- Neck pain.

- Dizziness and balance problems.

- Unusual feelings in the arms or legs (numbness or tingling).

- Muscle weakness and paralysis.

- Visual problems and involuntary movement of the eyes (nystagmus).

- Swallowing problems.

- Hearing loss and tinnitus.

People might also experience nausea (feeling sick), vomiting (being sick), insomnia (difficulty sleeping) and depression. For help with depression, your GP can advise you of mental health services.

Other associated Conditions with CM

Hydrocephalus is an excessive build – up of CSF in the brain.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colourless fluid that surrounds the brain and spine. Its main functions are to protect the brain (it acts as a shock absorber), to carry nutrients to the brain and to remove waste.

Spina Bifida is the incomplete development of the spinal cord and/or its protective covering. The bones around the spinal cord don’t form properly, leaving part of the cord exposed and resulting in partial or complete paralysis. Individuals with Type II CM usually have a myelomeningocele, a form of spina bifida in which the bones in the back and lower spine don’t form properly and extend out of the back in a sac-like opening.

Syringomyelia, or hydromyelia, is a disorder in which a CSF-filled tubular cyst, or syrinx, forms within the spinal cord’s central canal. The growing syrinx destroys the centre of the spinal cord, resulting in pain, weakness, and stiffness in the back, shoulders, arms, or legs. Other symptoms may include headaches and a loss of the ability to feel extremes of hot or cold, especially in the hands. Some individuals also have severe arm and neck pain.

Spinal curvature is common among individuals with syringomyelia or CM Type I. Two types of spinal curvature can occur in conjunction with CMs: scoliosis, a bending of the spine to the left or right; and kyphosis, a forward bending of the spine. Spinal curvature is seen most often in children with CM, whose skeleton has not fully matured.

CMs may also be associated with certain hereditary syndromes that affect neurological and skeletal abnormalities, other disorders that affect bone formation and growth, fusion of segments of the bones in the neck, and extra folds in the brain.

How common are Chiari malformations?

In the past, it was estimated that the condition occurs in about one in every 1,000 births. However, the increased use of diagnostic imaging has shown that CM may be much more common.

Complicating this estimation is the fact that some children who are born with the condition may not show symptoms until adolescence or adulthood, if at all. CM’s occur more often in women than in men and Type II malformations are more prevalent in certain ethnic groups.

How are Chiari malformations diagnosed?

Many people with CMs have no symptoms and their malformations are discovered only during the course of diagnosis or treatment for another disorder. The doctor will perform a physical exam and check the person’s memory, cognition, balance (a function controlled by the cerebellum), touch, reflexes, sensation, and motor skills (functions controlled by the spinal cord). The physician may also order one of the following diagnostic tests:

Computed tomography (also called a CT scan) uses X-rays and a computer to produce two-dimensional pictures of bone and vascular irregularities.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging procedure most often used to diagnose a CM. Like CT, it is painless and non- invasive and is performed at an imaging centre or hospital. MRI uses radio waves and a powerful magnetic field.

How are they treated?

Most people with CM are asymptomatic and it does not interfere with a person’s activities of daily living. In some cases, medications may ease certain symptoms, such as pain. The majority of people diagnosed with Chiari malformation will not require any surgical intervention.

However the key treatment for symptomatic Chiari malformations is surgery. Surgery will be considered and discussed on an individual basis and will not be suitable for everyone. The particular type of surgery will differ from person to person and you might need more than one operation as part of your treatment.

Your neurosurgeon will discuss your options with you.

The main type of surgery to treat Chiari malformations is to increase the space at the top of your spinal cord and back of your brain to allow more free movement of fluid between the brain and spinal canal.

Other treatment options include:

- Ventriculoperitoneal shunting: In patients with hydrocephalus, fluid in the brain can also be drained by the drilling of a small hole into the skull and a catheter (thin tube) being passed from the ventricle usually into the peritoneal cavity (the abdomen).

- Untethering: This is a process to divide a band of tissue that can hold the bottom end of the spinal cord down to the end of the spinal canal.

- Syringo subarachnoid shunt: In cases where the syrinx worsens or continues to be symptomatic once the Chiari malformation has been treated, a catheter can be placed into the syrinx cavity to drain it into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathway.

As with any form of surgery, there are risks associated with surgery to treat Chiari malformations. Sometimes, surgery leads to no improvement or even worsening of symptoms.

Your neurosurgeon will discuss these with you before your operation.

Possible risks of decompression surgery for Chiari malformation include:

- Spinal instability and need for further spinal surgery.

- Risk to life.

- Stroke or haemorrhage (bleeding).

- Paralysis of the arms and legs.

- Meningitis or other infection.

- Impaired speech.

- Memory loss or problems with thinking.

- Difficulty swallowing.

- Balance problems.

- Hydrocephalus.

- Seizures (although these are rare).

- Recurrence of symptoms.

However, most people who have surgery find that their symptoms improve afterwards.

Even if symptoms do not improve significantly, surgical treatment of Chiari malformations might prevent existing symptoms from worsening. The main aim of surgery is to re-establish free flow of CSF across cranio-cervical junction.

Some symptoms may persist such as Headaches – the operation is not meant to be curative for headaches and these may continue despite surgery.

Low pressure symptoms such as headaches, dizziness and nausea may also occur and be expected post operatively which usually can be managed conservatively.

Posterior fossa decompression surgery is performed on adults with CM to create more space for the cerebellum and to relieve pressure on the spinal column.

Surgery involves making an incision at the back of the head and removing a small portion of the bottom of the skull (and sometimes part of the spinal column) to correct the irregular bony structure.

A related procedure, called a spinal laminectomy, involves the surgical removal of part of the arched, bony roof of the spinal canal (the lamina) to increase the size of the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the spinal cord and nerve roots.

The surgeon may also make an incision in the dura (the covering of the brain) to examine the brain and spinal cord. Dura can be left open or sometimes additional tissue may be added to the dura to create more space for the flow of CSF and because of this there is a risk of CSF leak.

Hydrocephalus may be treated with a shunt system that drains excess fluid and relieves pressure inside the head. A sturdy tube that is surgically inserted into the head is connected to a flexible tube that is placed under the skin, where it can drain the excess fluid into either the chest wall or the abdomen so it can be absorbed by the body.

An alternative surgical treatment to relieve hydrocephalus is an endoscopic third ventriculostomy, a procedure that improves the flow of CSF.

A small perforation is made in the floor of the third ventricle to relieve pressure which improves the flow and relieves pressure by diverting the flow of CSF through a different channel within the brain.