This leaflet aims to give you some information about aortic valve disease and the options for treatment.

Aortic Valve Disease

Normal heart

RA = Right antrium

RV = Right ventricle

LA = Left atrium

LV = Left ventricle

PA = Pulmonary artery

Ao = Aorta

Aortic stenosis

The aortic valve is one of the main valves in the heart. It ensures that red blood (containing oxygen) flows from the main pumping chamber (the left ventricle) into the main blood vessel (the aorta) and out to the rest of the body. The valve closes after every heart beat so blood doesn’t leak back into the pumping chamber (left ventricle).

In aortic valve disease there is an abnormality of the aortic valve which means it doesn’t work properly.

The aortic valve can be narrowed in which case it won’t open properly (aortic stenosis) or it may not close properly and leak blood backwards into the main pumping chamber (aortic regurgitation). In some cases the valve may be both narrowed and leaky in which case the problem can be described as “mixed” aortic valve disease.

Bicuspid aortic valve

For further information please checkout the following video about the process of Bisuspid Aortic Valve.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve

In this video, we will be discussing the congenital heart disease condition known as bicuspid aortic valve. You may wish to view our video on the normal heart before watching this video.

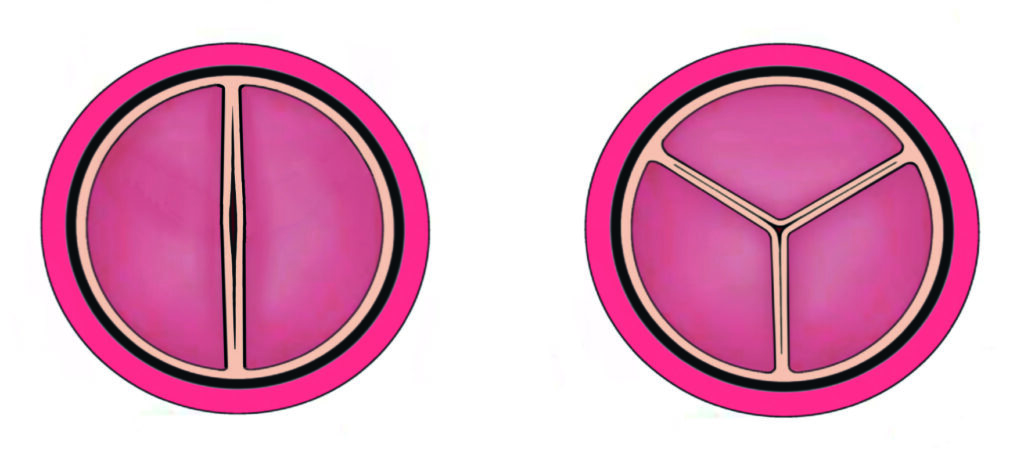

The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and aorta. Blood is pumped from the left ventricle through the aortic valve and into the aorta, from where it travels around the body. A normal aortic valve is made up of three leaflets. These leaflets open to let blood out of the heart and then close to prevent blood from returning to the heart from the aorta.

A bicuspid aortic valve has two leaflets rather than the usual three. One to two in every 100 people are born with a bicuspid aortic valve, and it can be inherited in some families. Bicuspid aortic valves can function normally and never require any treatment, but in many cases, the function of a bicuspid aortic valve deteriorates over time, becoming either narrowed or leaky or both.

Narrowing of the aortic valve is called aortic stenosis. In aortic stenosis, the valve does not open as well as it should, meaning the heart has to work harder to pump blood to the body. Mild or moderate aortic stenosis is usually well tolerated, and regular observation is all that is required. But when aortic stenosis becomes more severe, the muscle of the left ventricle may become thicker to enable it to pump more forcefully, and patients can develop symptoms such as breathlessness, chest discomfort, or feeling dizzy or even collapsing when exerting themselves.

Leaking of the aortic valve is called aortic regurgitation or aortic incompetence. Here, the aortic valve does not close properly, allowing blood in the aorta to return to the left ventricle. If severe enough, the blood that leaks back into the heart causes the left ventricle to enlarge, and if not treated in time, this causes the pumping function of the left ventricle to become impaired.

In many cases, a bicuspid aortic valve becomes both narrowed and leaky, and this is referred to as mixed aortic valve disease. In addition to problems with the function of the aortic valve itself, it is common for patients with a bicuspid aortic valve to develop enlargement of the aorta. This is called aortic dilatation. This doesn’t affect the function of the heart as such, but if the enlargement becomes severe, there is a risk of the aorta tearing, which can be life-threatening.

When either aortic stenosis or regurgitation becomes severe, treatment may be required. Occasionally, it is possible to treat aortic stenosis using a keyhole technique called aortic balloon valvuloplasty, which avoids the need to open the chest in an operation. In an aortic balloon valvuloplasty, a balloon is passed through the aorta to the aortic valve, where it is inflated. The expansion of the balloon forces the valve open.

In most cases, both aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation require replacement of the aortic valve by open-heart surgery. Depending on the situation, there are a number of potential options for surgical aortic valve replacement. Most commonly, the diseased bicuspid valve is removed, and a new artificial valve is sewn into place directly.

There are two types of aortic valve replacement. Mechanical aortic valve replacements are made of carbon and metal. They can usually last a lifetime but require lifelong blood thinning treatment with warfarin to prevent dangerous blood clots from forming on them. A tissue aortic valve replacement is made of animal tissue, usually from pigs or cows. The advantage of tissue valves is that they do not require lifelong blood thinning treatment, but the disadvantage is that they have a limited lifespan, especially in younger patients, and often require replacement in time.

The most appropriate valve type depends on a patient’s individual circumstances. In certain situations, an alternative operation, the so-called Ross procedure, may be appropriate, and we explain this in a different video.

About 2% of people have aortic valves that have 2 leaflets rather than the usual 3. These valves can function very well throughout life but do have a tendency to narrow and/or leak as people get older. As well as an abnormality with the valve, people with bicuspid aortic valves frequently have an abnormality with the main blood vessel (aorta) leaving the heart too. It may stretch (dilate) with the risk of a tear once it gets beyond a certain size or it may have a narrowing (coarctation). Your cardiologist or specialist nurse, will monitor this by scanning your valve and the aorta.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve

Aortic regurgitation (leak)

A leaky aortic valve makes the pumping chamber of the heart work harder than normal as it has to pump out the extra blood that has leaked back into the ventricle.

Aortic stenosis (narrowing)

Aortic stenosis means the left pumping chamber (left ventricle) has to work harder to pump blood through the narrowing. The leaflets may be thickened or stuck together.

Treatment for aortic valve disease

If the narrowing or leak is severe, the left ventricle can begin to struggle with the increased workload. If we see this during your follow ups, we may suggest treating the narrow or leaky valve. In aortic stenosis the leaflets are either thickened or stuck together.

- For narrow valves we can sometimes open up the valve with a keyhole procedure called a balloon valvuloplasty. This is usually a short-term fix and valves treated in this way almost always need an open heart operation to replace it at some point.

- Both narrow and leaky valves can be replaced in open heart surgery. there are different types of valve surgery, each with its own advantages and disadvantages which need to be discussed with your cardiologist.

Please see our other patient information leaflet “Aortic Valve choices” for more information.

Other issues

- Ongoing care: Young adults who were born with a heart problem are usually best cared for in a unit specialising in the care of this patient group (congenital cardiology). You will be monitored regularly, have heart scans (echocardiograms) and ECGs with possibly other tests if your cardiologist thinks it is necessary. You should not have any symptoms, unless the problem is severe. This is why it is important to come to your appointments – so we can pick up on problems before complications arise.

- Exercise: Regular exercise, to a moderate level, is encouraged. It is good for overall health and can also help to keep blood pressure lower / under control. Activities such as walking, cycling, and swimming are ideal and it is important to warm up. Unless the valve is only slightly narrowed it is often best to avoid really intense cardiovascular exercise, for example long distance running or sudden ‘bursts’ of strenuous activity (squash and sprinting for example). It is best to avoid power/weight lifting too.

If you are not sure whether any sport/activity is okay for you to do, please ask the adult congenital heart disease team caring for you for advice. - Endocarditis: All patients with aortic valve disease are at risk of infection in the heart (endocarditis). It is important that you have good dental hygiene and you visit the dentist every 12 months. Some people require antibiotics before invasive dental treatment. Please ask your doctor or specialist nurse if this applies to you. Due to the increased risk of infection entering the blood stream we would advise against body piercing and tattoos.

- Insurance: It can be difficult for people with congenital heart disease to get some types of insurance. Travel insurance may be more expensive and people who have congenital heart disease often struggle to get any type of life insurance. There are some more sympathetic insurers who can be identified and contacted through the Somerville Heart Foundation. We would recommend seeking advice from a specialist insurance advisor before applying for life insurance.

- There is a slightly increased risk of your baby having a congenital heart problem if you have it yourself, around 3-5%. If you have a bicuspid aortic valve this may be even around 10%. The overall population risk of having a baby with Congenital Heart Disease is around 1%. We can offer a specialised scan of your unborn baby’s heart at 18-20 weeks, which can detect any major abnormality of the heart.

- Pregnancy: Although pregnancy can be a risk in patients with severe aortic valve narrowing, patients with milder narrowing or leak usually cope very well. There are many issues relating to pregnancy for patients with aortic valve problems and it is VERY IMPORTANT you discuss things with your cardiologist before deciding to become pregnant.