On this page

- About this leaflet

- Alternatives to surgery

- General risks of surgery

- Specific risks of this surgery

- The operation for anterior vaginal wall prolapse (anterior colporrhaphy)

- Before the operation

- How the operation is performed

- After the operation – in hospital

- After the operation – at home

- More information

This leaflet firstly describes what an Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse is, it then goes on to describe what alternatives are available within our Trust, the risks involved in surgery and finally what operation we can offer.

About this leaflet

We advise you to take time to read this leaflet and write down any questions you have on the sheet provided (at the back of this leaflet). We can discuss them with you at our next meeting. It is your right to know about the operations being proposed, why they are being proposed, what alternatives there are and what the risks are. These should be covered in this leaflet.

What is an anterior vaginal wall prolapse

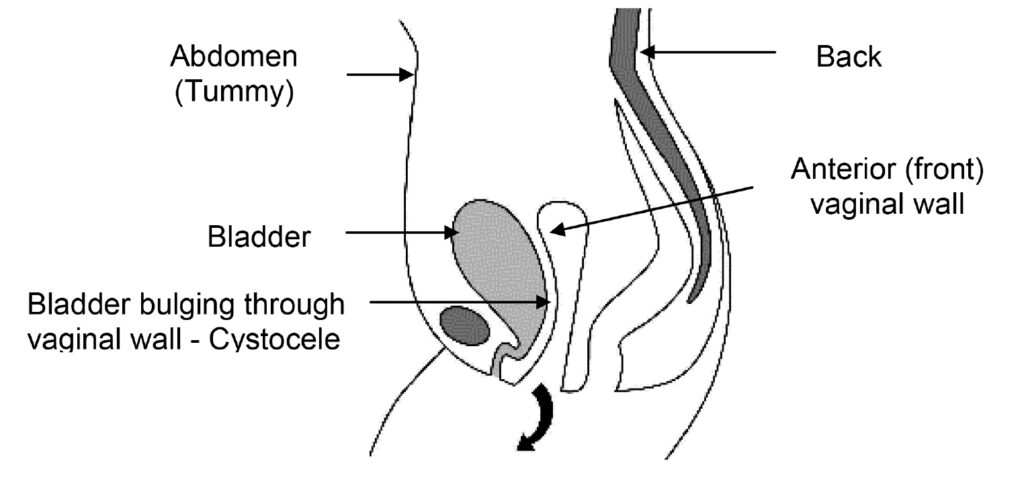

- Anterior means towards the front, so an anterior vaginal wall prolapse is a prolapse of the front wall of the vagina.

- The other name for an anterior vaginal wall prolapse is a Cystocele which describes the structure bulging into the vagina – the bladder (see diagram below).

- The pelvic floor muscles form a sling or hammock across the opening of the pelvis. These muscles, together with their surrounding tissue are responsible for keeping all of the pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, and rectum) in place and functioning correctly.

- Prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor muscles, their attachments or the vagina have become weak. This usually occurs because of damage at the time of childbirth but is most noticeable after the menopause when the quality of supporting tissue deteriorates. It is also related to chronic strain caused by heavy lifting and constipation.

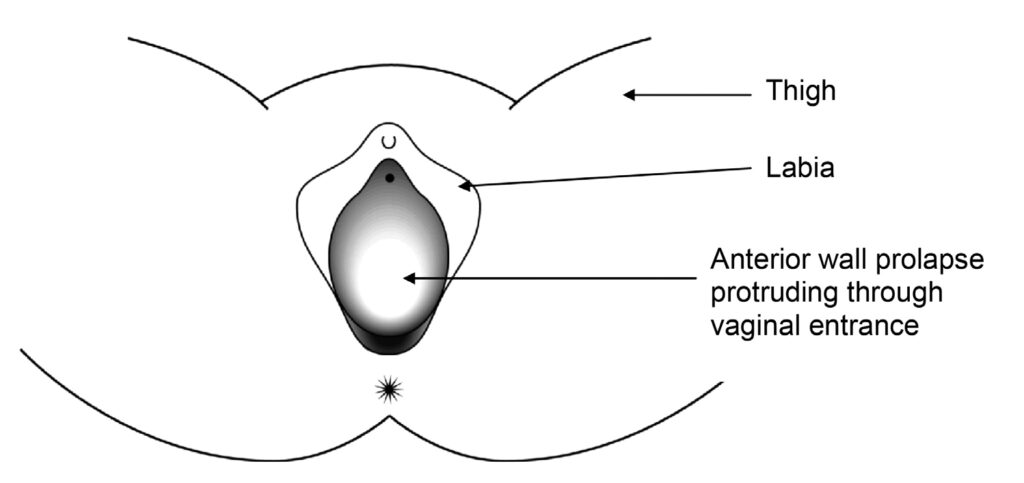

- When the Anterior Vaginal Wall is weak the bladder pushes down into the vagina causing a bulge. This sometimes can be large and push out of the vagina especially on straining e.g. exercise or passing a motion (Figure 1).

- A large Cystocele can often cause, or be associated with urinary symptoms such as urinary leakage, urinary urgency (strong and sudden desire to pass urine), having to go frequently, difficulty passing urine or a sensation of incomplete emptying.

- Some people have to push the bulge back into the vagina or lean forward in order to completely empty the bladder. Incomplete bladder emptying may make you prone to bladder infections (Urinary Tract Infection).

- Some people find that the bulge causes a dragging or aching sensation, or is uncomfortable when having sexual intercourse.

Alternatives to surgery

- Do nothing – if the prolapse (bulge) is not distressing then treatment is not necessarily needed. If, however, the prolapse permanently protrudes through the opening to the vagina and is exposed to the air, it may become dried out and eventually ulcerate. Even if it is not causing symptoms in this situation it is probably best to push it back with a ring pessary (see below) or have an operation to repair it.

- Pelvic floor exercises (PFE). The pelvic floor muscle runs from the coccyx at the back to the pubic bone at the front and off to the sides. This muscle supports your pelvic organs (uterus, vagina, bladder and rectum). Any muscle in the body needs exercise to keep it strong so that it functions properly. This is more important if that muscle has been damaged. PFE can strengthen the pelvic floor and therefore give more support to the pelvic organs. These exercises may not get rid of the prolapse but they make you more comfortable. PFE are best taught by an expert who is usually a Continence Nurse Advisor or Women’s Health Physiotherapist. These exercises have no risk and even if surgery is required at a later date, they will help your overall chance of being more comfortable.

Types of pessary

- Ring pessary – this is a soft plastic ring or device which is inserted into the vagina and pushes the prolapse back up. This usually gets rid of the dragging sensation and can improve urinary and bowel symptoms. It needs to be changed every 6-9 months, or earlier if there is any bleeding or discharge, and can be very popular; we can show you an example in clinic. Other pessaries may be used if the ring pessary is not suitable. Some couples feel that the pessary gets in the way during sexual intercourse, but many couples are not bothered by it.

- Shelf Pessary or Gellhorn – If you are not sexually active this is a stronger pessary which can be inserted into the vagina and again needs changing every 4-6 months.

General risks of surgery

- Anaesthetic risk. This is very small unless you have specific medical problems. This will be discussed with you.

- Haemorrhage. There is a risk of bleeding with any operation. The risk from blood loss is reduced by knowing your blood group beforehand and then having blood available to give you if needed. It is rare that we have to transfuse patients after their operation.

- Infection. There is a risk of infection at any of the wound sites. A significant infection is rare. The risk of infection is reduced by our policy of routinely giving antibiotics with major surgery.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). This is a clot in the deep veins of the leg. The overall risk is at most 4-5% although the majority of these are without symptoms. Occasionally this clot can migrate to the lungs which can be very serious and in rare circumstances it can be fatal (less than 1% of those who get a clot). DVT can occur more often with major operations around the pelvis and the risk increases with obesity, gross varicose veins, infection, immobility and other medical problems. The risk is significantly reduced by using special stockings and injections to thin the blood (heparin).

Specific risks of this surgery

- Damage to local organs. This can include bladder, ureters (pipes from kidneys to the bladder) and blood vessels. This is a rare complication but requires the damaged organ to repaired. This can result in a delay in recovery. It is sometimes not detected at the time of surgery and therefore may require a return to theatre. If the bladder is inadvertently opened during surgery, it will need catheter drainage for 7-14 days following surgery.

- Prolapse recurrence. If you have one prolapse, the risk of having another prolapse sometime during your life is 30%. This is because the vaginal tissue is weak. The operation may not work and it may fail to alleviate your symptoms.

- Pain. General pelvic discomfort, which usually settles with time, and tenderness during intercourse due to vaginal tethering or mesh erosion. Occasionally pain during intercourse can be permanent.

- Overactive bladder symptoms (urinary urgency and frequency). Usually gets better after the operation, but occasionally can start or worsen after the operation. If you experience this, please make us aware so that we can treat you for it. Stress incontinence may develop in up to 5% of patients.

- Reduced sensation during intercourse. Sometimes the sensation during intercourse may be less and occasionally the orgasm may be less intense.

The operation for anterior vaginal wall prolapse (anterior colporrhaphy)

- This operation has been performed for a long time.

- There is a high recurrence rate (symptoms returning) but the operation can be repeated.

- Because this prolapse involves the bladder, a test of bladder function (urodynamics) is sometimes required before the operation, especially if the prolapse is large or if you already have urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency or incontinence).

- The benefits are that you are likely to feel more comfortable, intercourse may be more satisfactory and you may empty your bladder more effectively.

Before the operation

It is recommended that you take a medication to soften your motions for at least three days before the operation. This will help to reduce the risk of you getting constipated after the operation and could mean you can go home earlier. Magnesium sulphate, Lactulose or Movicol would be suitable and you can obtain these from your General Practitioner. Your Gynaecologist may recommend local oestrogen if you are post-menopausal.

How the operation is performed

- The operation can be done with a spinal or general anaesthetic and you may have a choice in this.

– A spinal anaesthetic involves an injection in the lower back, similar to what we use when people are in labour or for a Caesarean Section. The spinal anaesthetic numbs you from the waist down. This removes any sharp sensation but a pressure sensation will still be felt.

– A general anaesthetic will mean you will be asleep (unconscious) during the entire procedure. - Your legs are placed in stirrups (supported in the air).

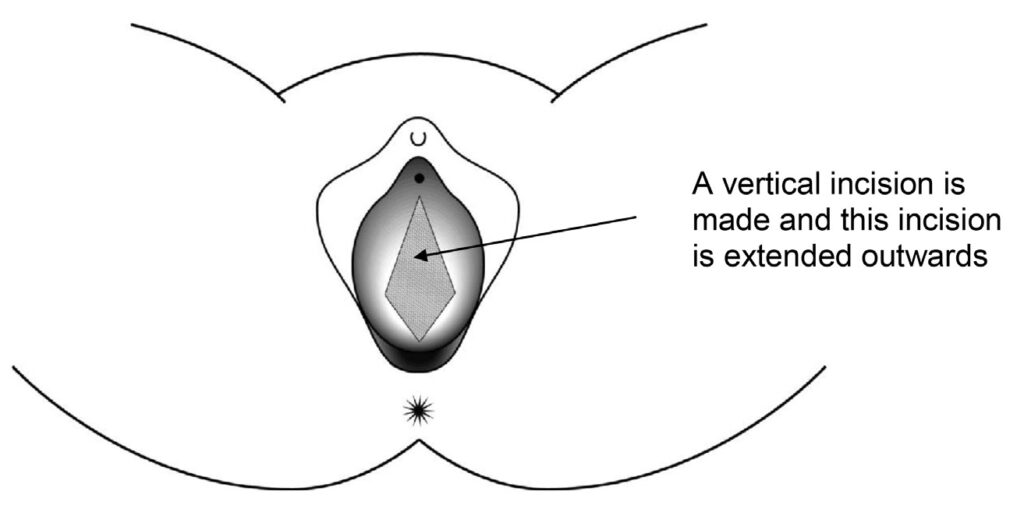

- The front vaginal wall is injected (infiltrated) with local anaesthetic.

- A vertical cut is made in the front wall of the vagina over the area of the bulge

(figure 2).

- The vaginal skin is then separated from the bladder.

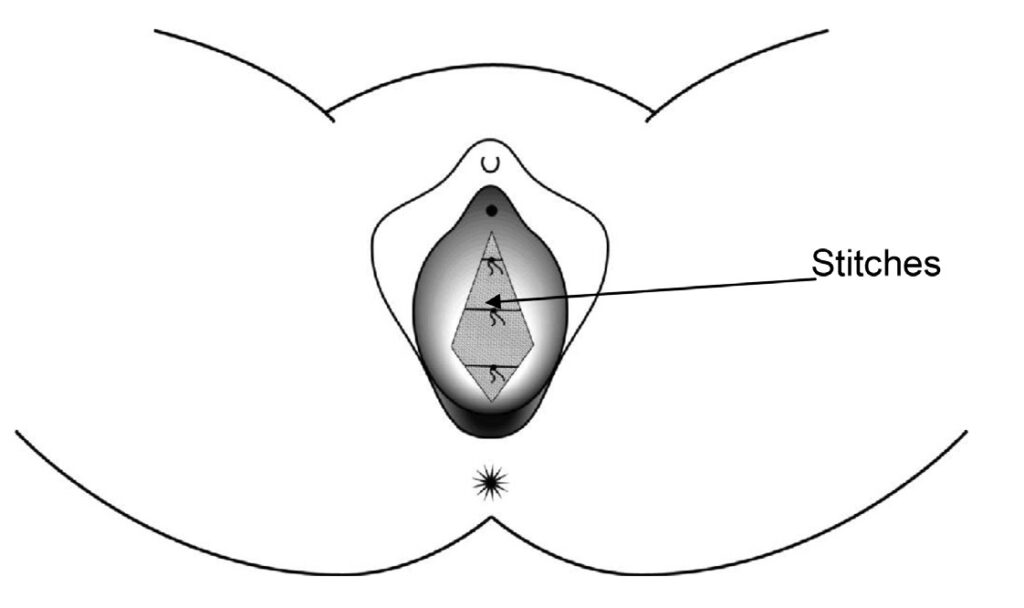

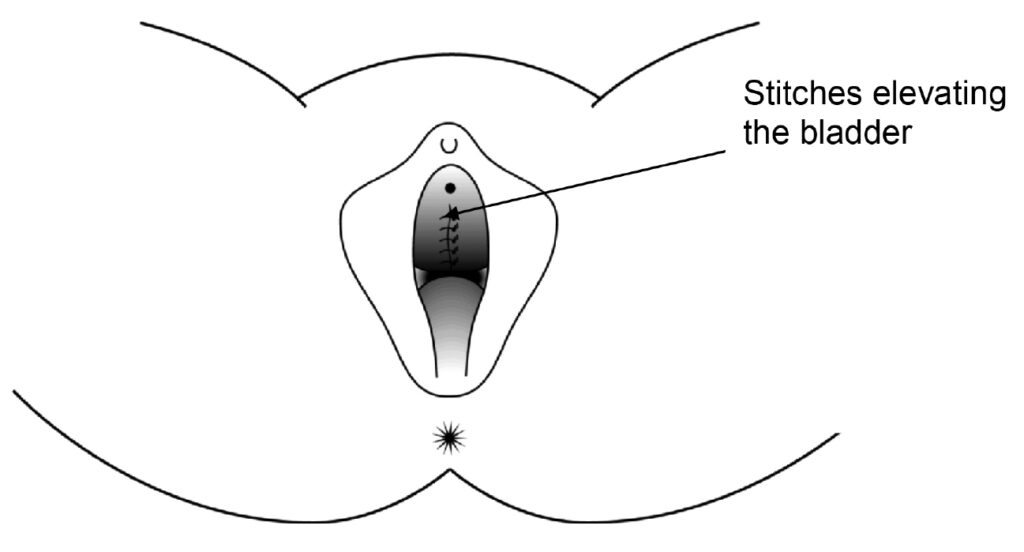

- Two or three repair sutures are placed in the tissues at either side of the bladder (figure 3).

- These stitches are then tied in the centre, bringing the fibrous tissue into the middle so that the bladder is elevated behind them and supported. This stops the bladder bulging into the front vaginal wall. Any excess vaginal skin is trimmed and then the vaginal skin closed with dissolvable stitches (figure 4).

After the operation – in hospital

- On return from the operating theatre you will have a fine tube (drip) in one of your arm veins with fluid running through to stop you getting dehydrated.

- You may have a bandage in the vagina, called a ‘pack’ and a sanitary pad in place. This is to apply pressure to the wound to stop it oozing.

- You may have a tube (catheter) draining the bladder overnight. The catheter may give you the sensation as though you need to pass urine but this is not the case.

- Usually the drip, pack and catheter come out the morning after surgery or sometimes later the same day. This is not generally painful.

- The day after the operation you will be encouraged to get out of bed and take short walks around the ward. This improves general wellbeing and reduces the risk of clots in the legs.

- It is important that the amount of urine is measured the first couple of times you pass urine after the removal of the catheter. An ultrasound scan for your bladder may be done on the ward to make sure that you are emptying your bladder properly. If you are leaving a significant amount of urine in your bladder, you may have to have the catheter re-inserted into your bladder for a few more days.

- You may be given injections to keep your blood thin and reduce the risk of blood clots, normally once a day until you go home or longer in some cases.

- The wound is not normally very painful but sometimes you may require tablets or injections for pain relief.

- There will be slight vaginal bleeding like the end of a period after the operation. This may last for a few weeks.

- The nurses will advise you about sick notes, certificates etc. You are usually in hospital up to four days.

After the operation – at home

- Mobilisation is very important; using your leg muscles will reduce the risk of clots in the back of the legs (DVT), which can be very dangerous.

- You are likely to feel tired and may need to rest in the daytime from time to time for a month or more, this will gradually improve.

- It is important to avoid stretching the repair particularly in the first weeks after surgery. Therefore, avoid constipation and heavy lifting. The deep stitches dissolve during the first three months and the body will gradually lay down strong scar tissue over a few months.

- Avoiding constipation:

– Drink plenty of water / juice

– Eat fruit and green vegetables especially broccoli

– Eat plenty of roughage e.g. bran / oats - Do not use tampons for six weeks.

- There are stitches in the skin wound in your vagina. Any stitches under the skin will dissolve by themselves. The surface knots of the stitches may appear on your underwear or pads after about two weeks, this is quite normal. There may be little bleeding again after about two weeks when the surface knots fall off, this is nothing to worry about.

- At six weeks gradually build up your level of activity. After three months, you should be able to return completely to your usual level of activity.

- You should be able to return to a light job after about six weeks. Leave a very heavy or busy job until 12 weeks.

- You can drive as soon as you can make an emergency stop without discomfort, generally after three weeks, but you must check this with your insurance company, as some insist that you should wait for six weeks.

- You can start sexual relations whenever you feel comfortable enough after six weeks, so long as you have no blood loss. You will need to be gentle and may wish to use lubrication (such as KY jelly) as some of the internal knots could cause your partner discomfort. You may wish to wait until all the stitches have dissolved, typically three months before having sexual intercourse.

- Follow up after the operation is usually six weeks to six months. This may be at the hospital (doctor or nurse), with your GP or by telephone. Sometimes follow up is not required.

BSUG (British Society of Urogynaecology) Patient Information Sheet Disclaimer:

This patient information sheet was put together by members of the BSUG Governance Committee paying particular reference to any relevant NICE Guidance. It is a resource for you to edit to yours and your trusts particular needs. Some may choose to use the document as it stands, others may choose to edit or use part of it. The BSUGs Governance Committee and the Executive Committee cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of the information contained in it. The placing of this information sheet on the BSUGs website does not constitute an endorsement by BSUGs.

We will endeavour to update the information sheets at least every three years.