This leaflet provides information for parents and carers about Ventricular Septal Defect in children and the management and treatment of this condition.

Ventricular Septal Defect (Large)

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the wall between the two main pumping chambers of the heart (the ventricles). Some patients have more than one VSD.

Here is a video explaining the condition:

Ventricular Septal Defect – YouTube

this video explains the congenital heart

condition ventricular septal defect you

may wish to view our video on normal

heart function before viewing this the

part of the heart that pumps blood to

the lungs via the pulmonary artery is

called the right ventricle

and the part of the heart that pumps

blood to the body via the aorta is

called the left ventricle the two

ventricles are divided by the

ventricular septum a hole in the

ventricular septum is called a

ventricular septal defect or VSD when a

VSD is present some of the blood that

should be pumped from the left ventricle

to the aorta passes through the VSD to

the right ventricle and then to the

pulmonary artery this means that more

blood flows to the lungs and flows to

the body the extra blood flow to the

lungs returns to the left side of the

heart and if the VSD is large enough

causes the left side of the heart to

enlarge the impact of a VSD largely

depends on its size at one end of the

spectrum a large VSD results in a large

amount of extra blood flow to the lungs

and may cause problems such as

difficulties with breathing and feeding

shortly after birth if larger vsts are

left untreated over time the extra blood

flow to the lungs can cause permanent

damage to the arteries of the lungs

are the other end of the spectrum when a

VST is small there may only be a very

small amount of extra blood flow to the

lungs such that the left side of the

heart does not become enlarged

you

closing a ventricular septal defect most

commonly requires open-heart surgery in

which a patch of material is sewn over

the hole preventing blood flowing

through it and allowing the enlarged

heart to reduce in size

in some cases in all the children and

adults smaller VSDs can be closed using

a keyhole procedure rather than

open-heart surgery however smaller vsts

may not need to be treated and some may

even closed by themselves when a small

bsd is left untreated observation over

time may be required because

complications occasionally occur for

example when the VSD is close to the

aortic valve the aortic valve can

develop a leak so that some blood that

has been pumped from the left ventricle

to the aorta leaks back into the

ventricle

there is also a risk of infective

endocarditis which means infection in

the heart on an untreated and VSD

you

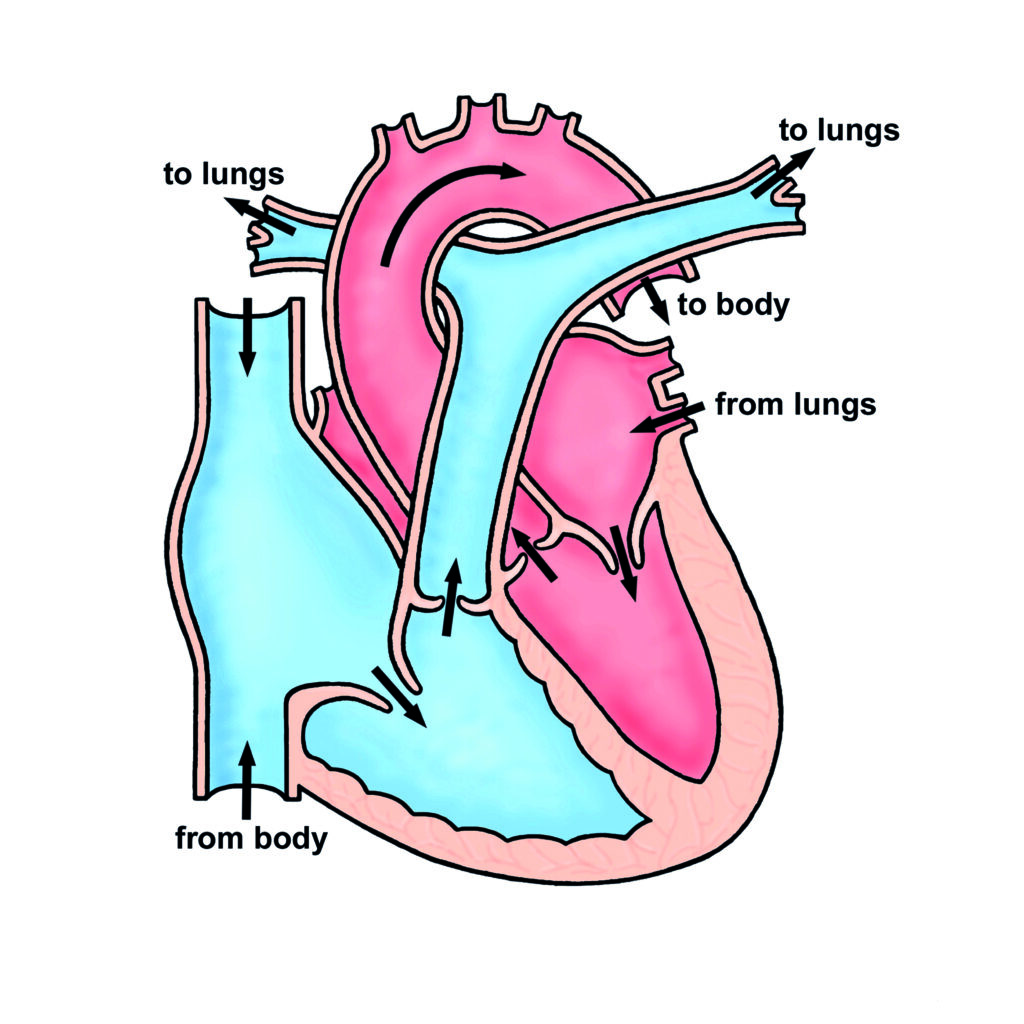

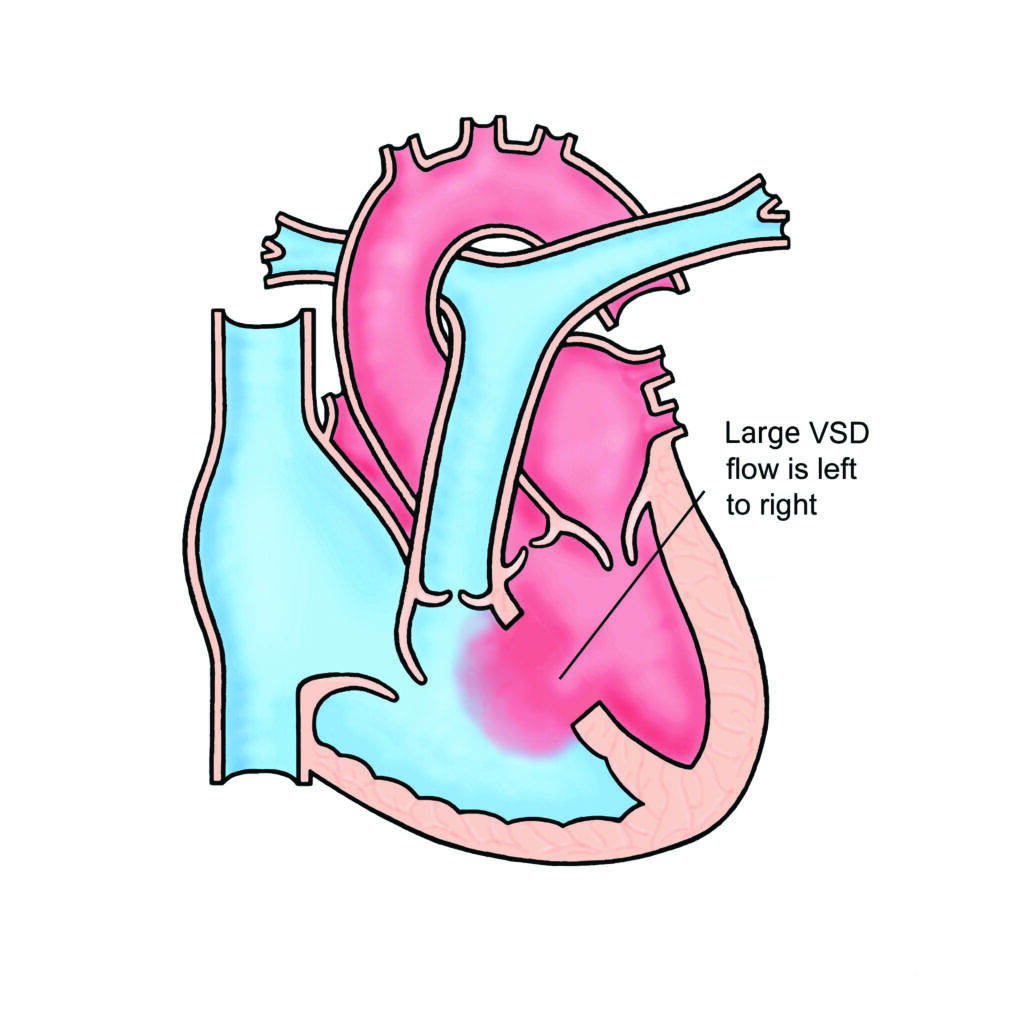

In the normal heart the left ventricle works at high pressure and pumps blood to the body and the right ventricle works at low pressure and pumps blood to the lungs. When there is a hole between the two ventricles (a VSD), blood flows from the left ventricle to the right ventricle through the hole. This causes the blood flow and the blood pressure in the right ventricle and in the arteries feeding the lungs (the pulmonary arteries) to be increased.

Babies with a VSD usually appear perfectly well in the first few weeks of life, but many gradually become breathless over the first month after birth because the increased blood flow to the lungs makes the lungs congested. Babies who are very breathless often cannot feed normally and may not gain weight easily because they put so much energy into breathing. Even quite big VSDs can gradually get smaller or even close off completely on their own as the child grows. However, if the VSD remains large enough to cause high blood pressure in the lungs for a long time (more than a year or so) there is a serious risk that the arteries in the lungs will become permanently damaged by the high blood pressure. This is a very serious complication (“pulmonary vascular disease”) and the child will gradually become more and more breathless and blue over a period of some years and will eventually die because of the damage to the lungs.

Tests

In most patients a simple test such as an ultrasound scan of the heart (“an echocardiogram”) is required to measure the size of the VSD and level of blood pressure in the lungs.

Treatment

Sometimes medicines can help to make the patient less breathless, but medicines cannot make the VSD smaller. If the VSD stays big as the child grows, surgery will be necessary.

In most cases it is possible to close the hole (or holes) but sometimes an operation, called a pulmonary artery band, is performed to reduce the amount of blood flowing to the lungs so that the bigger operation to close the hole can be delayed until the child is bigger. The operation to close the VSD involves opening the chest and sewing a patch of material over the VSD while the heart is stopped and its function is taken over by a machine (cardiopulmonary bypass). The operation takes about 4 hours and usually involves a stay in hospital of about 5-7 days, as long as the baby is feeding well. Most children are completely back to normal activities within 6 weeks after the operation. You will meet the surgeon prior to the operation , who will explain the operation in more detail including risks and potential complications.

Long term future

It is rare to need further treatment after surgery. Some patients will require medicines but this is usually only for a short time. Occasional outpatient visits are usually recommended even if the child is well, to make sure that the repair remains satisfactory as the child grows. They may be discharged later in childhood.

Most children lead completely normal lives after surgery to close a VSD.

General advice for the future

All patients with a VSD will be at risk of infection in the heart (called endocarditis) before surgery and if there is a small residual VSD after the operation there will still be a small risk of infection in the heart. Such infections may be caused by infections of the teeth or gums. It is important to look after your child’s teeth and visit the dentist regularly (every 6-12 months). Ear or body piercing and tattooing are best avoided as they also carry a small risk of infection which may spread to the heart.

For more information about endocarditis please see the link below: